As products of a digital society, you’ve probably been told to ‘go touch some grass’ at some point in your life. And maybe you should because there are actually a lot of great nature spots to check out in Singapore.

Forget the usual hiking spots that get crowded. Here are some alternative trails that take you to different worlds.

Learning Forest

Tucked in the corner of the Singapore Botanic Gardens is a century-old forest that has been landscaped to make it accessible to visitors. Though it is hardly a difficult hike, there is lots to learn about this dense forest. Walk through a boardwalk that takes you through freshwater forest wetlands, the canopies of ancient trees, a bamboo forest and a row of fruit trees.

FIND IT

753 Tyersall Ave, Singapore 257700 (nearest entrance is the Tyersall Gate)

Seletar Fishing Village

More than just a hidden gem, Seletar Fishing Village is only explorable at low tide. Start the hike from the nearby Rower’s Bay Park where you can walk by the waterside of Lower Seletar Reservoir. The actual fishing village, Jenal Jetty is still in operation – you can find huts and boardwalks by the water but it is not accessible to the public unless you sign up for an official tour.

However there are viewing points a few yards from the village and at low tide, many hikers and explorers actually trek down to the beach to walk on the sandbars. It is also the perfect spot to view the sunset and sunrise – that is if the low tide syncs with the timing! Do check timings for the tide before exploring to avoid being disappointed.

FIND IT:

The best way to access the park is to walk from Rower’s Bay Park.

Dover Forest

Sometimes you don’t have to look far for the best trails. They might just be right there in the neighborhood – next to the MRT station for example. Dover Forest is a unique secondary forest in Clementi – and there are two sections: Dover Forest East and Dover Forest West. Though just a few meters away from Dover MRT station, expect to trek through thick vegetation, heritage trees and even a stream. Because there isn’t a clear entrance or proper trails in the forest, it’s well advised to go on a guided tour. Best to check out this not-so-hidden gem before Dover Forest East is cleared in the near future to be used for building HDB flats.

FIND IT:

The best way to enter Dover Forest East is through Ghim Moh Link, and to enter Dover Forest West, follow the walkway when you exit Dover Station and walk through the field on your left.

Thomson Nature Park

Take a trail in this park which takes you through the ruins of a former village and a farm in Singapore. Though the route is relatively short, there’s plenty to see as you stroll through the pages of history. See remnants of houses, outdoor stoves, farmland and even the track where Singapore’s first Grand Prix was held in 1961.

Keep your eyes peeled for wildlife around the park, such as the shy and elusive banded langur, mischievous macaques, monitor lizards, squirrels and birds.

Read more: Secret City: Thomson Nature Park – Singapore’s former farm and Grand Prix track

FIND IT:

Upper Thomson Rd

Tampines Eco Green

Tampines might be a very dense neighbourhood but this mature estate holds some (green) gems too. Just meters away from a major road and residential blocks is the lush Tampines Eco Green. The hidden park has several rustic trails surrounding a mini marsh and also spots – made from reclaimed timber and old wood – where people can quietly and discreetly birdwatch.

FIND IT:

Tampines Ave 9, Singapore 520491

Rifle Range Nature Park

|

coconuts.co

The newly opened Rifle Range Nature Park is another to add to the pretty parks list. Part of the Central Nature Park Network, the park serves as one of the…

14 Nov 2022 |

The Lost Ark

Update: Due to the erratic weather in the first quarter of the year, the area is now flooded and difficult to get to. The fallen tree “ark” may not be structurally safe anymore so do be careful when hiking in this area

The dreamy-sounding Alexandra Woodland might sound like something out of storybooks but somewhere tucked on the side of the Green Corridor near Hang Jebat Mosque, is a plot of unprotected and almost untouched land with overgrown vegetation and a natural pond. One of the highlights of trekking in this area is the mysterious ‘Lost Ark’ structure made with fallen trees in the area. There’s a deck which faces the pond where you can stop for a quick thermos coffee break. Not a lot is known about the history of this place but judging from the small estates surrounding the woodlands which are full of colonial-era black and white houses, the clearing was probably a rustic recreational garden or park, similar to the ones in England during the time.

FIND IT:

Find a manmade dirt path next to the Green Corridor near Hang Jebat Mosque and follow the trail

Kingfisher Lake

In case you didn’t know, Gardens by the Bay is huge – really, really huge. In the sprawling gardens, there are plenty of mini-gardens within. One of the best ones (and also hidden ones) is the Kingfisher Lake. The main star is the lotus lake but follow the side stream and you’ll find a nice and lush spot – near the giant kingfisher – perfect for a little breather or contemplation. Other worthy spots in Gardens by the Bay include the Chinese Gardens with its landscaped terrain, water features and “moon gate” as well as the Serene Gardens on the far end of the park where there is a mini waterfall feature and is a little quieter and peaceful from the more bustling areas.

FIND IT:

Walk towards Satay by the Bay and you’ll stumble upon the lake.

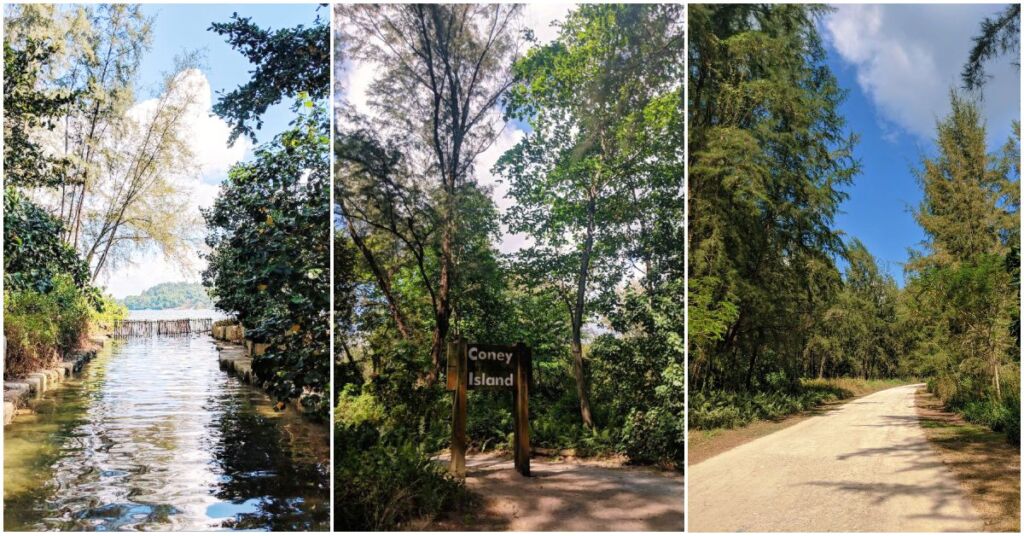

Coney Island

Sure it’s a popular jogging track and outdoor spot for the weekend crowd but Coney Island has its little hidden and secret spots too if you veer just a little away from the main track that cuts through the island. Explore the hidden beaches – each beach area has a different feel to it – and if you’re up for it, you can try to find the abandoned beach villa which used to belong to the Aw Brothers of Haw Par Villa fame.

Read more: Did you know that Coney Island used to be a leisure resort?

FIND IT:

Head to Punggol Point Park and follow the boardwalk to the West Entrance of the island.

Windsor Nature Park

Everyone goes to MacRitchie Reservoir for its views and diverse trails – which is also why it’s one of the most crowded places on weekends. If you don’t fancy your jungle walk to be disrupted by a bunch of young adults discussing how to do a proposal (true story), check out one of MacRitchie’s “side” parks, Windsor Nature Park. With streams, an eco pond and several trails where you can catch a glimpse of birds and other wildlife, you can still get your hiking fix without all the extra noise.

FIND IT:

30 Venus Drive, Singapore 573858

Hampstead Wetlands Park

Another result of the colonial hangover are names of streets and things named after actual places in England. Well, this place in Seletar is one of them. Though it’s been revamped quite recently, the park still retains a bit of its rustic charms. A dedicated trail takes you into the mini woods before you view the pond. There’s an observation deck on the boardwalk where you take a closer look at the pond and even spot some birds in the area.

FIND IT:

1 Baker Street, Singapore 799977

Keppel Hill Reservoir

There’s a lot of history that surrounds this spot that it should be something everyone visits at least once while in Singapore. The start of the trail is a spectacle in itself. Start at the Seah Im Carpark near the food centre to check out an abandoned WWII bunker before climbing up the steep slope next to it for the second highlight. Don’t worry, there are ropes for you to hold on to as you make your way up. Keppel Hill Reservoir is located just around the corner from where you climb up. Formerly used as a source of water, and then later as a private swimming pool, the reservoir today has probably seen better days. But it’s still a sight to see, hidden for years and unmarked on most maps.

FIND IT:

Start from the carpark at 2 Seah Im Road, Singapore 099114.

Seng Chew Quarry

You’d never think you’ll find a lake with magical water, but there’s one right in Bukit Gombak. This disused quarry was a product of Singapore’s quarrying days which ceased by the 90s. Over the years, it’s been filled with rainwater and just sitting there casually behind some residential flats. To get there you just have to take a short walk from Bukit Gombak MRT to Block 383 and climb up the slopes facing the block. Follow the longkang and it will lead you to the quarry. You’ll be surprised at the size of it – it’s much bigger than Keppel Hill Reservoir. In the past, the water of the quarry is said to bring luck so taxi drivers would park near the drainage to wash their cars with the water.

FIND IT:

Start from Bukit Gombak MRT and walk through Bukit Batok West Ave 5 until you reach Block 383.

Yunnan Garden

Universities are hardly the place you’d think of going for a hike but planted within Nanyang Technological Univesity (NTU) is a beautifully manicured park inspired by classical Chinese gardens. There are gazebos, mini ponds, rock sculptures, and even a man-made lake, but the main highlight of the park is the picturesque waterfall feature.

FIND IT:

1 Nanyang Drive, Singapore 637721

RELATED:

|

coconuts.co

After being gazetted as a conserved building, the new developers of Golden Mile Complex are looking to preserve the facade and distinct features of the iconic building. And while we…

11 Jul 2023 |

⸆⸉|Midnights Oct21 (@folkloreforevrr)

⸆⸉|Midnights Oct21 (@folkloreforevrr)